|

|

Authentic Classical Music |

BEETHOVEN

A N E C D O T A L “When I was still small, I spent three years here in Vienna learning to play the violin with Joseph Böhm, a musician from Beethoven's circle of acquaintances told us. I lived in Böhm's house, and Mrs. Böhm always supervised me when I was practising. A frequent visitor to this hospitable household was an old violinist, Grünberg, who had played for many years in Beethoven's orchestra. Grünberg told of how Schuppanzigh, the concert master, complained to Beethoven during the first rehearsal of a new composition that a certain part had been so badly written for the left hand that one could barely play it. Whereupon Beethoven barked at him: ‘When I wrote this part, I was aware of being inspired by Almighty God. Do you think that I can take your tiny fiddle into account when He is speaking to me?’” |

THE COMPOSER ON HIS VIOLINCONCERTS |

In 1880, for instance, Joseph Hellmesberger, the

famous Viennese violinist, teacher of Fritz Kreisler and Franz Kneisel,

declared that the violin concerto of Johannes Brahms was “written not

for but against the violin”, and he predicted, that it would speedily

be consigned to oblivion.

That same year when Joachim introduced the work to Berlin, all the principal critics damned it unmercifully and the consequen-ces of that fiasco were that for the next decade, the major Symphony Orchestras of Europe when engaging Joachim as soloist, did so with the stipulation that he must not play the Brahms concerto. In 1953 the conductor Eugene Ormandy states: “With my audiences and all the violinists who play under me, the Brahms is now the most popular of all violin concertos, not excepting the Beethoven.”

Johannes Brahms “I will not find my true place in musical history until at least half a century after I am gone. Bach died in 1750 and he was completely forgotten until Mendelssohn revived him, more than seventyfive years later. And it was more than a hundred years after his death that Joachim succeeded in popu-larizing his monumental works for violin alone. Also the stupendous Beethoven violin concerto was neglected for fully fifty years after his death until Joachim revealed its wonders to the musical world. No composition in our day has been more reviled than my own violin concerto; Joachim and I brought it out at the Gewandhaus sixteen years ago, and still the music societies, when they engage Joachim as soloist, do so with the stipulation that he must not play my concerto. I have put new vine into old bottles and the Philistines cannot forgive me for that. I know that the violin con-certo will find its real place, but it will at least take five decades, and it is much the same with my symphonies, piano concertos and many other works.” Brahms

“Brahms has been dead ten years but he still has many detractors, even among the

best musicians and critics. I predict, however, that as time goes on, he

will be more and more appreciated, while most of my works will be more and

more neglected. Fifty years hence, he will loom up as one of the supremely

great composers of all time, while I will be remembered chiefly for having

written my G minor violin concerto.

Brahms was a far greater composer than I am for various reasons. First of all he was much more original. He always went his own way. He cared not at all about the public reaction or what the critics wrote. The great fiasco of his D minor piano concerto would have discouraged most composers. Not Brahms! Furthermore, the vituperation heaped upon him after Joachim introduced his violin concerto at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1880 would have crushed me. Another factor which militated against me was economic necessity. I had a wife and children to support and educate. I was compelled to earn money with my compoitions. Therefore, I had to write works that were pleasing and easily understood. I never wrote down to the public; my artistic conscience would not permit me to do that. I always composed good music but it was music that sold readily. There was never anything to quarrel about in my music as there was that in Brahms. I never outraged the critics by those wonderful, conflicting rhythms, which are so characteristic of Brahms. Nor would I have dared to leave out sequences of steps in progressing from one key to another, which often makes Brahm’s modulations so bold and startling. Neither did I venture to paint in such dark colours, à la Rembrandt, as he did. All this, and much more, militated against Brahms in his own day, but these very attributes will contribute to his stature fifty years from now, because they proclaim him a composer of marked originality. I consider Brahms one of the greatest personalities in the entire annals of music.”

Max Bruch |

|||||||

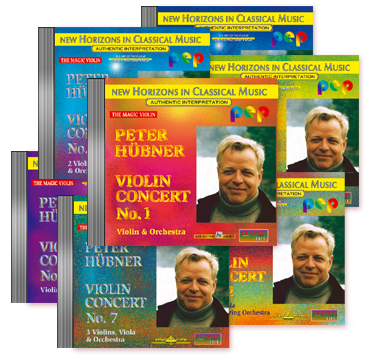

CLASSIC-Life: Herr Hübner, you have created 7 violin concertos which – I believe I

can hear – are somehow related to each other.

PETER HÜBNER: Yes, these 7 violin concertos all refer to each other. This was important, as they develop contrapuntally. The 4th violin concerto, for instance, is an integration of the 1st and 2nd violin concerto, the 5th violin concerto is an integration from the 1st and 3rd, the 6th violin concerto is an integration from the 2nd and 3rd, and the 7th violin concerto is an integration from the 1st, 2nd and 3rd violin concerto. From the 2nd violin concerto onwards there is also a respective fugue in up to seven parts, which is played by the orchestra. CLASSIC-Life: Which violin concerto do you yourself like best? PETER HÜBNER: From my point of view, each of these violin concertos has of course its very own value. From a musical theoretical aspect, the first 3 violin concertos are surely the simplest – starting with the first. But for the start, I find the 3rd violin concerto the most attractive. But here, even my friends differ in their opinions. From the 4th violin concerto on, recording wasn’t easy, due to the contrapuntal use of the different violin concertos, as the orchestra wasn’t to be pushed too far into the background – after all, besides many further motifs and themes, it was continuously playing a fugue in seven parts – and the solo violins and/or the solo viola had to be clearly audible, were to stand out from each other tonally, and merge again, and were, above all, to harmonise with each other in the continuity of the complex of themes. As is well known, the means for a stereo version on CD are limited – even if we already use Dynamic Space Stereophony. CLASSIC-Life: So, to start off with, you would recommend the 3rd violin concerto? PETER HÜBNER: Personally, yes, I would, but I know others who recommend a different order. A friend, for example, regularly listens to the 7th. For me this is extraordinary, because he isn’t a music expert. From my point of view, I would have thought that the contrapuntal use in the concerto would only be most interesting for a music expert. But the musical complexity and the counterpoint obviously have a strong effect on the subconscious. CLASSIC-Life: Could you say something about your solo violin – that “Magic Violin”, as the label calls it? PETER HÜBNER: Yes, I can tell you a few things. I had and have a number of violin sounds in digital form at my disposal – natural, artificial and mixed. I wasn’t looking for a violin which is a copy of the usual violin, but rather the convincing performance of music through a sound which is fundamen-tally related to that of the violin. That applies for one in a certain extent to the range and also to the process of swinging in as well as the overwave spectrum. However, I neither wanted any scratching nor the feeling that you could hear some sort of wood. I also wanted a strong sound which, not only as far as volume goes, but also its over wave spectrum, could assert itself with an individual musical statement within the polyphony of the orchestra sound. And I think, all in all I was lucky. In the beginning you might miss that sound quality in this violin which you believe to hear in a conventional wooden violin, but once you have got used to the sound, listening at a later stage to a conventional piece of music on a wooden violin, it sounds subjectively more like a fiddle, and in comparison seems weak and less convincing. When choosing an instrument and/or its sound, I am mainly concerned with the individual living multi-layered powers of persuasion. I think it is worthwhile to listen and to get to know all seven violin concertos step by step, as they conceal a compositional-musical development which is only gradually revealed. |

|||||||||

| CLASSICAL MUSIC GROUP |

| p r e s e n t s |

| PETER HÜBNER GERMANY’S NEW CLASSICAL COMPOSER |

| Authentic Interpretation |